How Emotional Neglect Shapes a Child’s Inner World

How Emotional Neglect Shapes a Child’s Inner World

Children do not begin life with the capacity to understand or regulate their internal states. Their emotional and regulatory systems mature over time, which means they rely heavily on caregivers to interpret, soothe and organise their experiences. When adults respond consistently and with attunement, children gradually learn how to manage distress and build a stable sense of self.

When emotional cues are dismissed or blocked, the developmental trajectory shifts. A child who reaches out and is met with stonewalling, being told to manage on their own or being sent away while distressed receives a clear message: their feelings are not tolerated, and seeking support is unsafe. Eventually, they stop trying. Their energy moves from connection to self-preservation. They begin suppressing rather than processing, withdrawing rather than expressing. These patterns often become the blueprint for how they operate in later relationships and stressful situations.

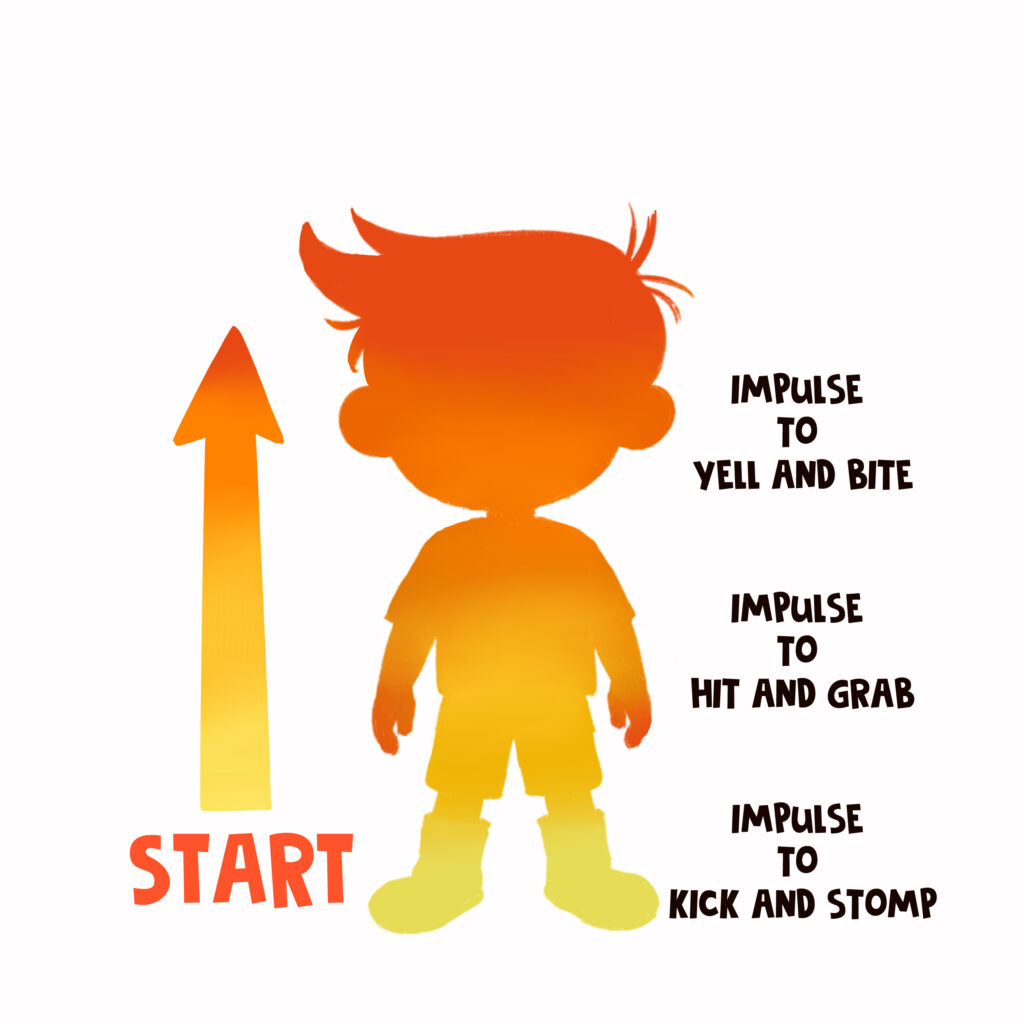

Because children lack the cognitive and neurological structure to regulate without support, suppressing emotions comes at a cost. The nervous system remains in a heightened state far longer than it should. Over years, this chronic stress response increases the likelihood of developing significant problems, including anxiety disorders, depressive symptoms, irritability, sleep disruption and a range of physical conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia and even certain heart complications. These are not simply coincidences; they reflect how prolonged emotional strain embeds itself in the body’s functioning.

The idea that children “toughen up” by handling emotions alone is a misunderstanding. What actually happens is that they adapt by shutting down parts of themselves to cope. The child becomes skilled at masking, minimising and staying silent, but they do not become emotionally resilient. Instead, they grow into adults who struggle to identify their own needs, feel undeserving of support or assume that their emotional life is a private burden.

What truly strengthens a child’s long-term adaptability is not the removal of hardship but the presence of a caregiver who can meet distress with clarity and steadiness. When a parent stays engaged rather than withdrawing, the child learns that difficult feelings are workable rather than overwhelming. This experience becomes the foundation of an internal voice that says, “I can handle this, and I am worth understanding.”

For parents or caregivers reflecting on their own patterns, the key is not perfection. It is willingness. The willingness to notice when you are disconnecting, to pause before pushing a child away during their hardest moments and to recognise that these interactions shape more than just behaviour. They shape the child’s beliefs about safety, worth and connection.

Emotional availability is not a soft skill. It is a form of guidance that directly influences a child’s psychological structure and physical health. By responding with engagement rather than avoidance, caregivers give children the tools to manage themselves without having to shut down parts of who they are in order to survive.